March is Brain Injury Awareness Month, and Tab Journal asked Chapman University MFA alum and former staff Jason Thornberry to share his experiences. You can follow Jason @thornberryjm on Twitter.

TBI & what is normal?

After my traumatic brain injury, when I returned—pale and disoriented—from the flickering grey atmosphere of the hospital to the real world, I felt completely alone. With a passport stamped in my own blood, I sought to resume my normal life. But what was normal—and what of my life remained?

My relationships were scattered on the wind of my lengthy recovery. The wind moaned, pushing me toward my mother and away from my father. My father, with whom I argued violently over the telephone that night—the night I was injured. I recall one of us hanging up on the other. Was it me? Was it him? I don’t remember. I remember an overwhelming rush of silence filling the void at the end of our call—the statement implied by the force of a hand smashing a landline back into its cradle. The muted click as the call was severed. Yes, maybe it was him.

My mother blamed him for inspiring me to drink so much that night—the night a pair of strangers savagely beat me. The night that changed my life forever. When I was released, my father visited me. He posed with me for a picture in the grass outside my mother’s home, standing behind my wheelchair. I sat stiffly, feeling his hands on my shoulders. A few days later, we argued over the phone once more, and nine years passed before we saw each other again. Without him, I depended on my mother to guide me through the arduous depths of my outpatient therapy and my lengthy recovery. My mother and I became close for the first time. Later, when I exerted my independence by moving out of state with my then-girlfriend-now-wife, cracks developed in my relationship with my mother, opening the ground between us. I haven’t spoken with her in months.

Before my father and I fell out, and before that fate-soaked night, I lived with my two best friends. We were in a band together: a trio. We recorded and performed and made plans to tour the country together, to flourish beyond the anonymity of our day jobs together. They visited me there in my flickering grey room. As I looked up at them from my hospital bed, we talked about the future. When I was released, they moved away, taking our friendship with them. Twenty-two years later, I bumped into one. She said our other bandmate was officially homeless now, living somewhere on the streets of Los Angeles. The overwhelming rush of silence filling the void as I received this information reminded me later of that night when I held the telephone. She broke the silence to ask me what I was doing, gesturing toward the papers on the coffeehouse table. I said I was writing.

Reading with TBI. Writing with TBI.

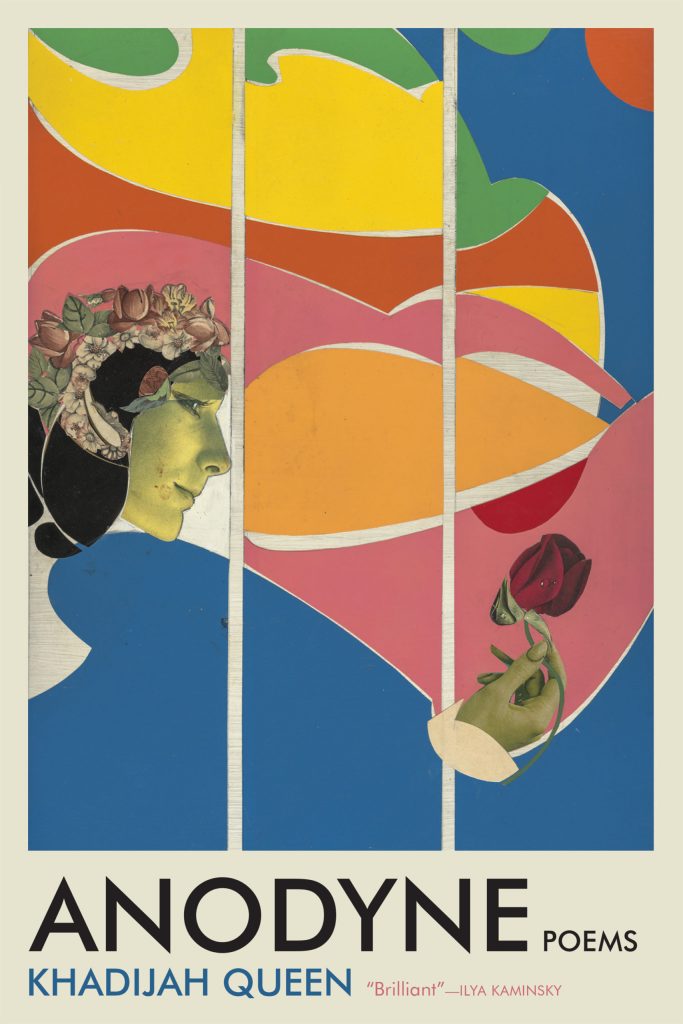

I find my voice through writing and reading. I seek alternate worlds—not in deep futuristic space, but here—where I can live in someone else’s skin, where I can breathe the same air, sharing their triumphs and struggles, seeing things from their perspective. I inhabit the deceptively simple, sculpted sentences of Toni Morrison and the hideous suffering of her characters; I observe the muddled turmoil of humanity through the eyes of Verlyn Klinkenborg’s blinking tortoise; I soar like Wordsworth’s bees, murmuring by the hour in foxglove bells. I live again. And again.

Thinking of embodiment (and of empathy), I revisit the words of Gregory Orr. When Orr describes, in his poem “Trauma (Storm),” hunkering down within “the cave of self,” the place where he escapes the raging world, I see my trauma made flesh. I experience, again, the glowing pain I felt after waking from my coma. I feel the brusquely indifferent hands of nurses transferring my twisted form from gurney to gurney and place to place like a portable autopsy. I hear the monotonous beeping of MRIs and CT scans in arctic chambers of the hospital and the pathokinesiology study I underwent before a panel of puzzled physicians. The physicians took notes, muttering amongst themselves as they watched me hobbling in pain, crossing the room in front of them like a tortoise. By meditating on Orr’s poetry, I feel liberated from memories of my past by living in his skin, donning the mask of Cain he wore after the accidental death of his brother and—and by the subsequent death of his mother, two years later.

Orr uses poetry, he says, to survive the “emotional chaos, spiritual confusions, and [the] traumatic events that come with being alive.” When I found myself in this same silent cavern of isolation, confusion, and guilt, I recognized that writing was my only way out in the years following my injury. And I find now, in Orr, a kindred spirit. His words remind me I’m not alone.

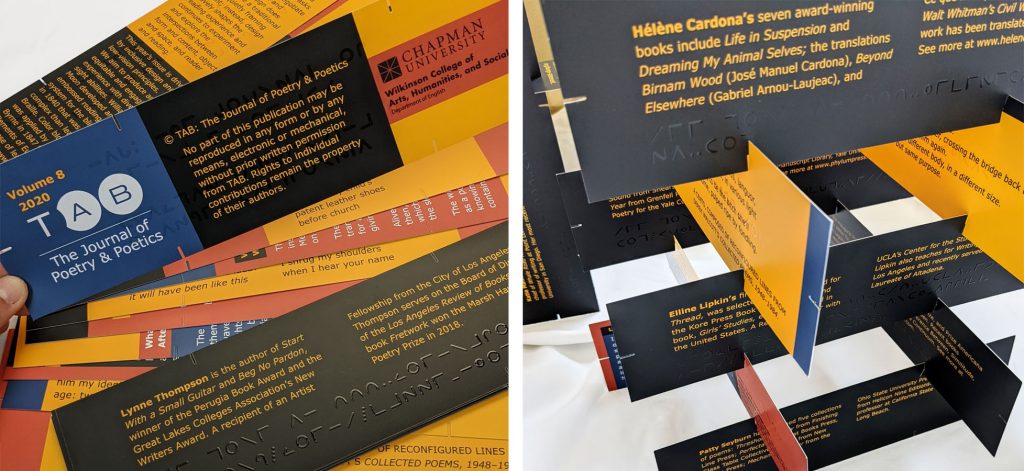

Read poems by Jason Thornberry

“Residue of Yesterday,” OPEN: Journal of Arts & Letters (January 2022)

Two Poems: “California” & “My Landlord’s Landlord,” Poor Yorick Literary Magazine (December 2021)

Three Poems: “Cobwebs,” “The Foghorn,” and “Toward Medallions of Broken Glass”, The Antonym Magazine (May 2021)