March is Autoimmune Awareness Month. Tab Journal acknowledges the many poets who have and written about autoimmune disease.

Autoimmunity, Chronic Illness, Poetry

One of Editor Anna Leahy’s early poetry professors was Mary Swander, who sought treatment for allergies in 1983 and instead ended up with autoimmune dysregulation in which her body couldn’t tolerate certain foods, pollutants, and orders. In 1998, Swander edited a collection of essays by writers with chronic illness. Much and little has changed since then.

Here’s an excerpt from “In a Dream,” an earlier poem by Mary Swander but one that might be thought to foreshadow chronic illness:

Your feel it diving into you,

lodge between muscle and bone,

move one spiny fin.

Your whole body goes numb.

Poet Suzanne Edison also edited an autoimmunity-themed collection that combines her poems with visual explorations. Moreover, The Body Lives Its Undoing includes not only the perspectives of patients but also family, physicians, and researchers.

A couple of years ago, Bustle ran a list thirteen poems about chronic illness, featuring work by Hieu Minh Nguyen, Max Ritvo, and others.

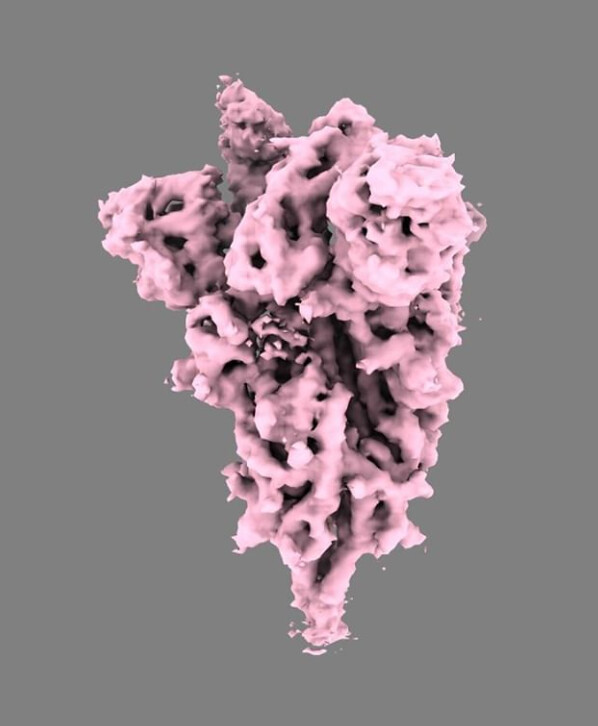

Autoimmunity, Covid, Poetry

Earlier this month, poet and nonfiction writer Meghan O’Rourke wrote in Scientific American, “When the first wave of coronavirus infections hit the U.S. in March 2020, what kept me up at night was not only the tragedy of the acute crisis but also the idea that we might soon be facing a second crisis—a pandemic of chronic illness triggered by the virus.” O’Rourke argues in this article and in her new book The Invisible Kingdom that covid long-haulers are a game-changer for all those who’ve faced autoimmune dysregulation, the difficulty of getting a diagnosis, and the frustration of inadequate treatment and research funding.

O’Rourke’s own autoimmune disorder emerged in the wake of her mother’s terminal illness, something she wrote about in The Long Goodbye and in poems like “Ever.” The opening lines of the poem “The Night Where You No Longer Live” suggests such a shift in well-being:

Was it like lifting a veil

And was the grass treacherous, the green grassDid you think of your own mother

Was it like a virus

Did the software flickerAnd was this the beginning

Jen Karetnik, a contributor to Tab Journal (Volume 8, Issue 4), has written about the covid long haul at About Place Journal. The opening lines capture the sense of chronic autoimmune dysregulation:

lignum vitae, wood

so dense it doesn’t floatI’ve been reduced to not being able to stand up in the shower

poetic, considering how much

the wood has given to ocean travelEven reading a book is challenging and exhausting

an escaped ornamental

pruned to maintain a narrower profileI don’t understand what’s happening in my body

Kadijah Queen wrote of the pandemic for Harper’s:

Asthma and other chronic health issues keep both my son and my mother at risk; my mother takes so much medication we have an Excel spreadsheet to keep track. They’ve sheltered in place for eight weeks. I’m at risk, too, but I try not to think about it.

…

Used to be I could rest through fibromyalgia flares, recover. Now I depend on balms and pills to keep going through the pain. Dr. Bob’s, vapor rub, Papa Rozier balm, Aleve PM, Benadryl, charcoal bath salts, lavender oil. Make a pleasure of coffee or espresso for the fatigue. Bless Nespresso machines. Elvazio, Melozio, Hazelino, Voltesso. Solelio for something lighter, if I have to wake up but know I’ll need sleep later.

Her latest poetry book, Anodyne. It’s title refers to something that alleviates pain. Anodyne won the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America. Queen, who has fibromyalgia, told Boulder Weekly the following when the book came out:

I think in terms of health and disease and disability, there’s this really negative language around it,” Queen says. “When in fact we’re all gonna deal with health issues, so why are we hiding it, trying to suppress talking about it, saying, ‘It’ll be OK,’ or just medicating it? And why is the language around it so ugly? Why do we not have more natural and compassionate ways of talking about the aging process? Why are we not creating more places for care that don’t feel like you’re just dropping your parent off somewhere to die? … I think we’re missing real care.

If O’Rourke is right, we’ll understand more in the months and years to come. And yet Edison’s words from “Here, Ellipses” will always be a crucial question:

And we wonder

Who is essential expendable…

And we call each other saying—How

you holding up

How you holding

How you

How