Tab Journal has published several visual poems over the last two years. Perhaps because we use design thinking in our approach to poetry, we’re interested in the definitions, practices, and possibilities for poets who are consciously using visual elements to create meaning. Tab Communications Coordinator Lydia Pejovic talked with five visual poets for the March issue: Maria DeGuzmán, Kylie Gellatly, Monica Ong, Donna Spruijt-Metz, and Keith S. Wilson.

Here, she talks in further detail with Kylie Gellatly.

Lydia Pejovic: Your visual poetry is also erasure poetry. How do you find your source material for these poems?

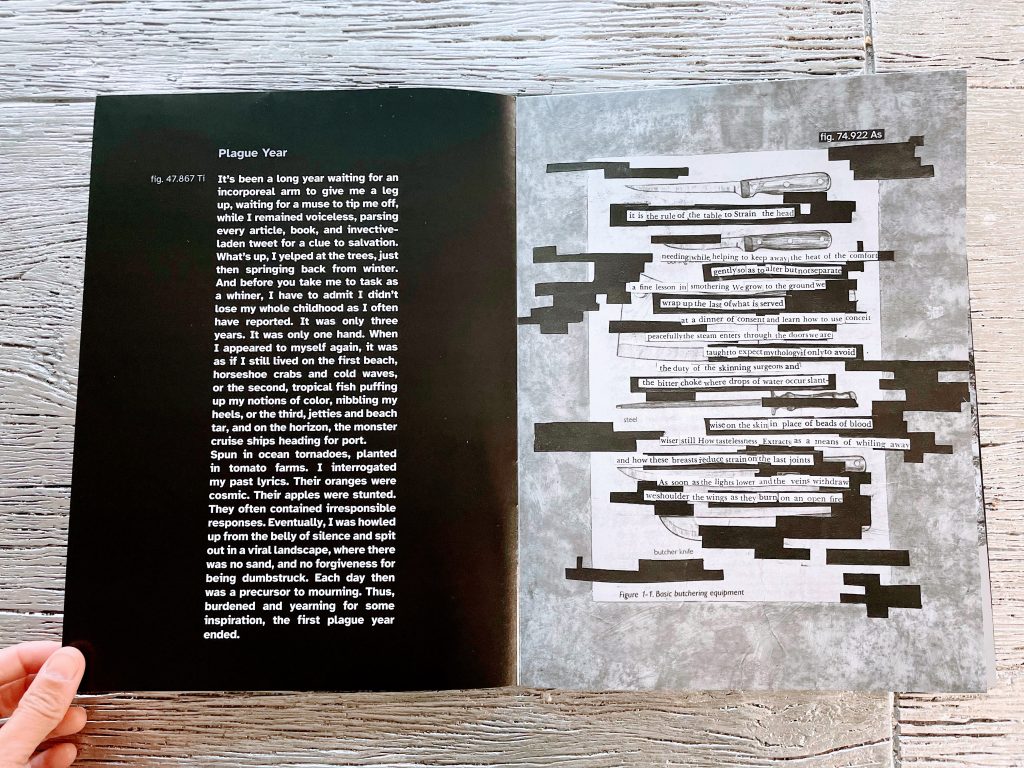

Kylie Gellatly: Erasure is subversive by nature, which gives the source text a very specific role in the work. In this project, I wanted the process to enact the themes and vice versa, and thus made sure that the source texts matched the process in content in order to explore the fuller concept. Because this work is not erasure in its traditional sense, but an extraction of content from its context, I was interested in exploring what exactly those differences mean. The removal of substance from its content provided the mode for me to work with the concepts of gastronomy, consumption, human and animal relations, and gender.

I selected two cookbooks and a hunting guide. Using multiple texts helps me think of them as ingredients, each with its own flavor and chemical makeup, thus interaction. One cookbook was chosen as a cornerstone of hierarchical and masculine cuisine in the restaurant industry (Escoffier), while another was chosen as an eclectic “kitchen garden” book on herbs and spices that includes both histories and recipes (Matter of Taste, Humphrey). The hunting guide is a book on the ethics of hunting and provides a language that, when mixed with the Escoffier’s recipes and the historical text in Humphrey, rounds out the palette. By working with, I am questioning and undermining the language we use around food—how disoriented the ingredient is from its source, how cooking is all action and transmogrification, it is about power of subject over object, and command-based communication: mince garlic, peel carrots, or remove the meat from the bone.

Lydia Pejovic: How do you create these pieces? How does poetry work differently based on whether you create it by hand or by using digital software?

Kylie Gellatly: What I love about working with found poetry is that what I notice when I come to the page is always different and depends on the headspace I am in. It makes the headspace something I can work with while creating these poems by curating a space to be coming from. I’ve been doing a lot of research and reading about the concepts I am working with, which has provided a curated space from which to write from, as these poems (so far) are not explicitly depictive of the subject, but are coming out of the questions that arise. As I currently am an omnivore and worked for a time as a butcher, the question is most often some form of how do I feel about this? but is always working with this tension.

The content and the process of this project is inseparable from the content, while the product—the visual poem—is almost incidental. It’s something I question a lot. With my first book, The Fever Poems, it was truly incidental and I was often saying, “I need to glue it down so the words don’t blow away.” Which is still true, but with this new project, the poems themselves are so dependent on the performance of creating them. With regard to the final visual poem, I am still figuring out how the image works with the text and how I want to direct the image with it. Sometimes it feels too obvious to have an illustration of an animal or butchery on the page—even if the poem is not depicting it, the process is. It will take time for me to discover how that signature, so to speak, is working on the finished piece or what else the image can do. Like any art form, the next piece is informed by the one that preceded it.

Visual poetry requires a lot of trust in one’s own creative process and I put a lot of trust into what words and fragments jump out at me from the page.

Kylie Gellatly: In erasure poetry, that trust is usually heightened, as the words that don’t jump off the page are blacked out, but I am using the ones that grab my attention as the seed or prompt of the poem. When first coming to the page, I am careful not to read any of the text from left to right, but rather top to bottom, looking for non-sequential chains of language to work with. A big part of the creativity in this work is being able to hold the word, seeing its potential, while also suspending its context and connotations. This can be more challenging if the book you’re working with is one that is more familiar to you. The confines of the work—of having to work with what is there, or of choosing to search the whole book for one word—are what make this process so rewarding and full of discovery.

Lydia Pejovic: I’ll add that you also put a lot of trust in editors—you trusted Tab Journal and worked with Creative Director Claudine Jaenichen because the January 2022 design didn’t allow for four colors, for that vibrancy of your original. I’m suggesting, perhaps, what a page can be.

Kylie Gellatly: The image is usually the product of an emptied page—one that has been whittled to a frame after most of the words have been cut out. The emptied pages, when blacked out beneath, signify an erasure, while the ones that have an image laid underneath and are blacked out around the frame, work more as a window or an under the skin depiction. The latter is used more in this project, as what we tend to engage most with is what is under the skin of the animal.

Previously in Visual Poetry: Monica Ong

Next Up in Visual Poetry: Keith S. Wilson